During the second world war the US army would fly their cargo planes onto small remote islands in the Pacific. On these islands the US army had built runways, controls towers and radar to ensure a smooth operation and enable them to supply their war effort with food, water, ammunition and general goods. These islands were inhabited by native, primitive, indigenous people that would, from afar, observe the planes flying in to deliver cargo. These natives studied the rituals that were employed to deliver such riches such as aircraft marshals signalling grounded aircraft, traffic-control tower operators wearing headphones and speaking into microphones.

As the war drew to an end the US army dismantled their operations on these islands, taking their control towers, radar and equipment with them. Having observed this behaviour the indigenous people believed that if they could mimic what they saw that they would be able to summon riches from these magical flying tin cans again to their islands. So, with the available materials around them, wood, sticks, mud and leaves, they set to build radar, control towers, aircraft and even headphones to mirror what they had observed.

These native groups have been named “cargo cults”. They believe that these riches come from the gods and that by mimicking their observations that if they wait with faith that eventually the planes will land again and they will be rich and happy.

This psychological phenomena is now being seen in both science and technology. In particular the Agile movement in tech and software development practices where the focus is on complying with the rituals without fully understanding the 'why' or the goals associated with the practices. It's not uncommon for an organisation to be complicit in cargo cult Agile by pushing teams towards certification, adherence to an Agile methodology or standardising on practices and tools organisation-wide. With endeavours of “everyone must be Agile by the end of the [insert arbitrary time]” (a phrase that, of course, means nothing at all). Teams end up with a fixation on the process and doing the Agile rituals; daily stand-ups, retrospectives, sprint planning, story points etc and expect that following the process will deliver value. Over time teams struggle to make any significant gains with their newly found “Agile” ways of working. More importantly though, doing so can actually be harmful to an organisation; financially and culturally. Consider Nokia spent $1B to enact their failed transformation.

During such a "transformation” eager teams are keen to report that they're complicit and towing the line. They expose metrics that paint a picture of success e.g. number of people certified, number of deployments of software, number of features delivered (or story points). On the outside everything is reported green but on the inside not much has changed when it comes to customer success, innovations or revenue increases. Much like a watermelon it's green on the outside but red on the inside.

I truly believe that people, in general, have the best intentions but sadly it's very popular to bash, or ridicule, Agile or a particular Agile methodology due to the proliferation of cargo culting. The misinterpretation and commercialisation of Agile has resulted in its unpopularity in recent years amongst product engineering teams. There is value in Agile ways of working of continuous discovery/delivery, operating in small batch sizes and short feedback loops to inspect and adapt and delivery value for customers iteratively. So how do we shift focus away from cargo cult Agile and pull out real value from the original intent of the Agile manifesto?

Solve your own problems, not somebody else's

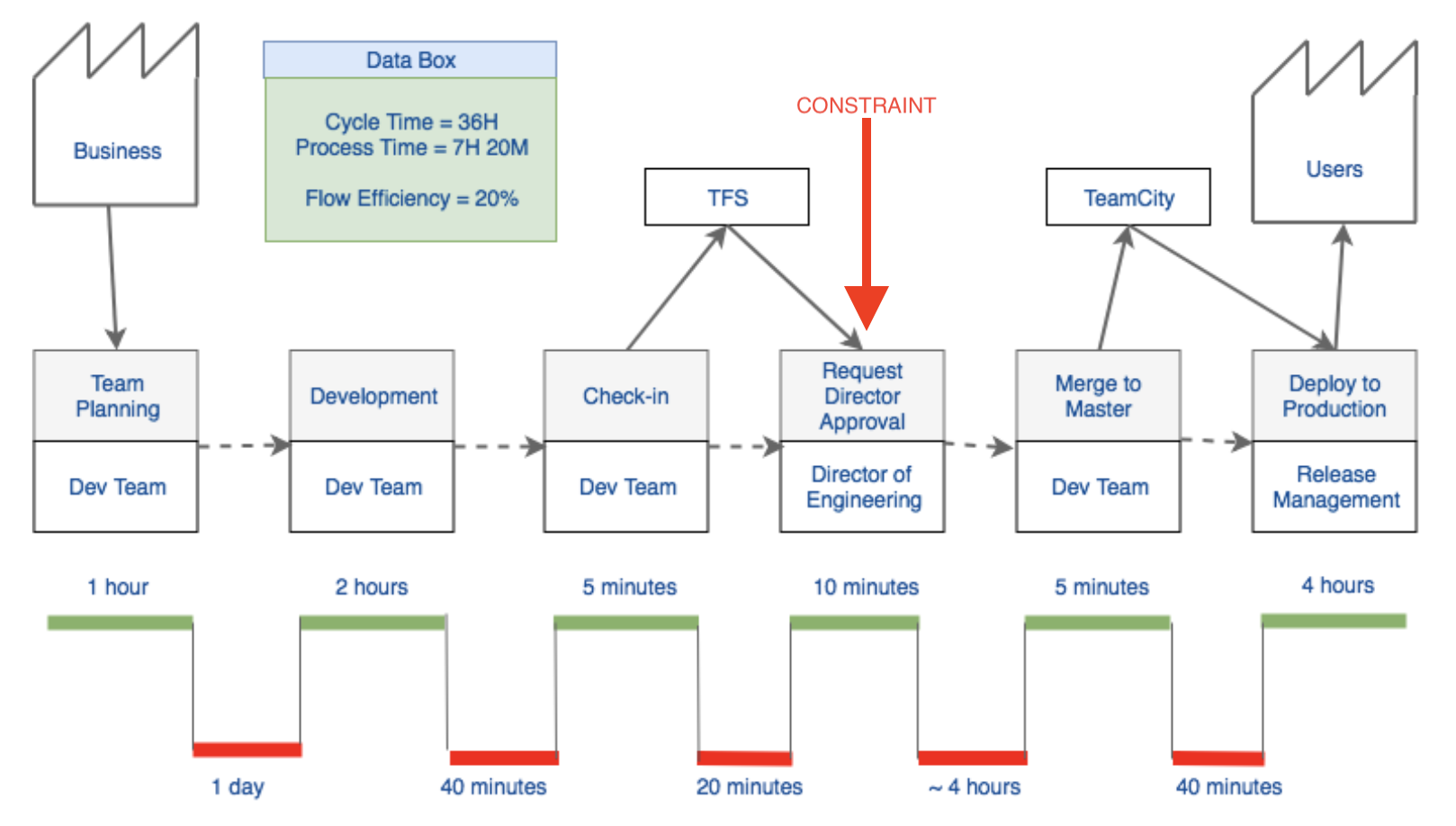

Far too often teams are focussed on proxy metrics that they think account for agility. On the surface, metrics such as the number of deploys or number of story points delivered may seem like a good blanket indicator for agility. The problem with such metrics is that they're most often a proxy to agility. If deployment velocity isn't your blocker then it's the wrong metric. Hiring more teams, putting more work through the funnel or increasing work in progress (WIP) will likely increase these metrics organically but unintentionally. When teams truly own their processes and pipeline they should have the quantitive insight that allows them to identify their blockers to agility. When we understand the full value stream we can identify these blockers. Perhaps, in your organisation, the risk and compliance process is the blocker to delivering value at speed? Or legal copy approval? Once we know what the blocker is, in our own context, we can start to put in place metrics to drive improvements in those key areas that are specific to our organisation.

Making it practical: Encourage teams to build value stream maps and annotate them with time metrics. Print them out and hang them on the wall near your team. Use them in planning to ensure you're focussed on the next priority blocker. An example below:

Psychological safety and slack time (reduced WIP)

84% of digital transformations fail. Studies have largely attributed this to cultural issues and resistance to change. Personally, I don't find that people necessarily resist change, more so that they don't feel safe to do so. People need to be encouraged to push back and question things. This only comes when there is an environment where people feel the psychological safety to do so. How leaders react to suggestions, feedback and initiative are critical to encourage this type of environment. The Project Aristotle study by Google concluded that the most significant indicator of effective teams is psychological safety over that of who is on the team and how they work. Google characterises psychological safety as:

Psychological safety: Psychological safety refers to an individual’s perception of the consequences of taking an interpersonal risk or a belief that a team is safe for risk taking in the face of being seen as ignorant, incompetent, negative, or disruptive. In a team with high psychological safety, teammates feel safe to take risks around their team members. They feel confident that no one on the team will embarrass or punish anyone else for admitting a mistake, asking a question, or offering a new idea.

Even with a culture of psychological safety, teams need slack time to enact change, try new things, experiment and own/improve their processes. This includes what is typically classified as “non-feature” work. More often than not a drive for “Agile” results in more work in progress (WIP) as there is an expectation to continue at pace whilst at the same time asking teams to make improvements. We know that increased WIP is a significant blocker to value creation (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KR7Y8IUgyyA) and process improvement. A motorway with 100% utilisation is not optimal...it's a traffic jam. Give teams significant slack time to enact change and make improvements to the value stream.

Making it practical: Measure your teams psychological safety with an anonymous questionnaire (Google provide some good details on how to do that here (https://rework.withgoogle.com/print/guides/5721312655835136/)). Making improvements takes understanding and coaching but awareness and measurement are critical first steps.

Making it practical: Track work in progress and put WIP constraints in place on your teams kanban boards.

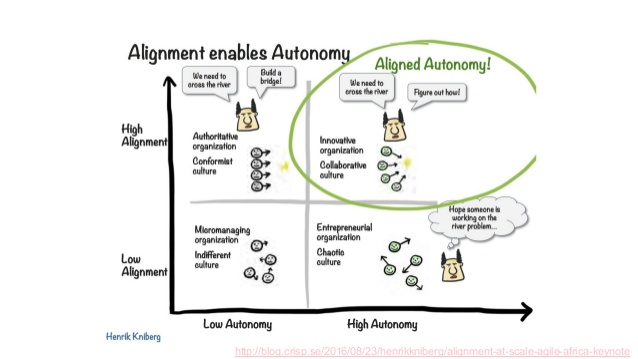

Cautiously standardise

In driving Agile ways or working, organisations are often in one of two camps. Either they try and drive alignment by standardising or dictating ways of working (via processes and policy). Or teams are given a maturity model and encourage to work their way up the model at their own pace. Both can be dangerous. Dictating working practices is the antithesis of Agile. Give teams a level-set understanding of Agile and empower them to use their own context and their own learning to experiment, iterate and improve. Push decision making downwards to the team and empower them to own their process. Cautiously standardise and understand the impact of being prescriptive with tools and processes. Of course there's a balance to be struck with a proliferation of tools across teams and giving teams the autonomy to make the decisions needed to make them most effective. Aim to be in the top right corner of aligned autonomy (high alignment, high autonomy):

Making it practical: Mandating tools (e.g. JIRA) should not be associated with an Agile journey. If you have to standardise on a tool for valid reason then don't lock teams down to how they should use it.

There is no template for agility. An Agile methodology is just a starting point for a set of practices. Whilst there is value in looking externally to learn from other organisations, such as the Spotify model, your business, your culture and your people are unique to you and your business. Capitalise on your uniqueness and your own 'why'. Once you have a team that understands the why behind their processes, and are autonomous, and have reduced WIP, and is psychologically safe - they will focus on the constraint, they will elevate it (and subvert all else) and will ensure their pathway to continuous improvement is honed around that.